These vibrant illustrations of the Virgin Mary, Jesus Christ and angels come from an Ethiopian psalter purchased for Special Collections last summer. Ethiopia is one of the oldest Christian countries, having been converted in the 4th c by missionaries from Syria, but then isolated for centuries from other Christian countries. This isolation meant that traditions and liturgy changed much more slowly in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church than in places subject to outside influence – and so can seem archaic and unfamiliar to us.

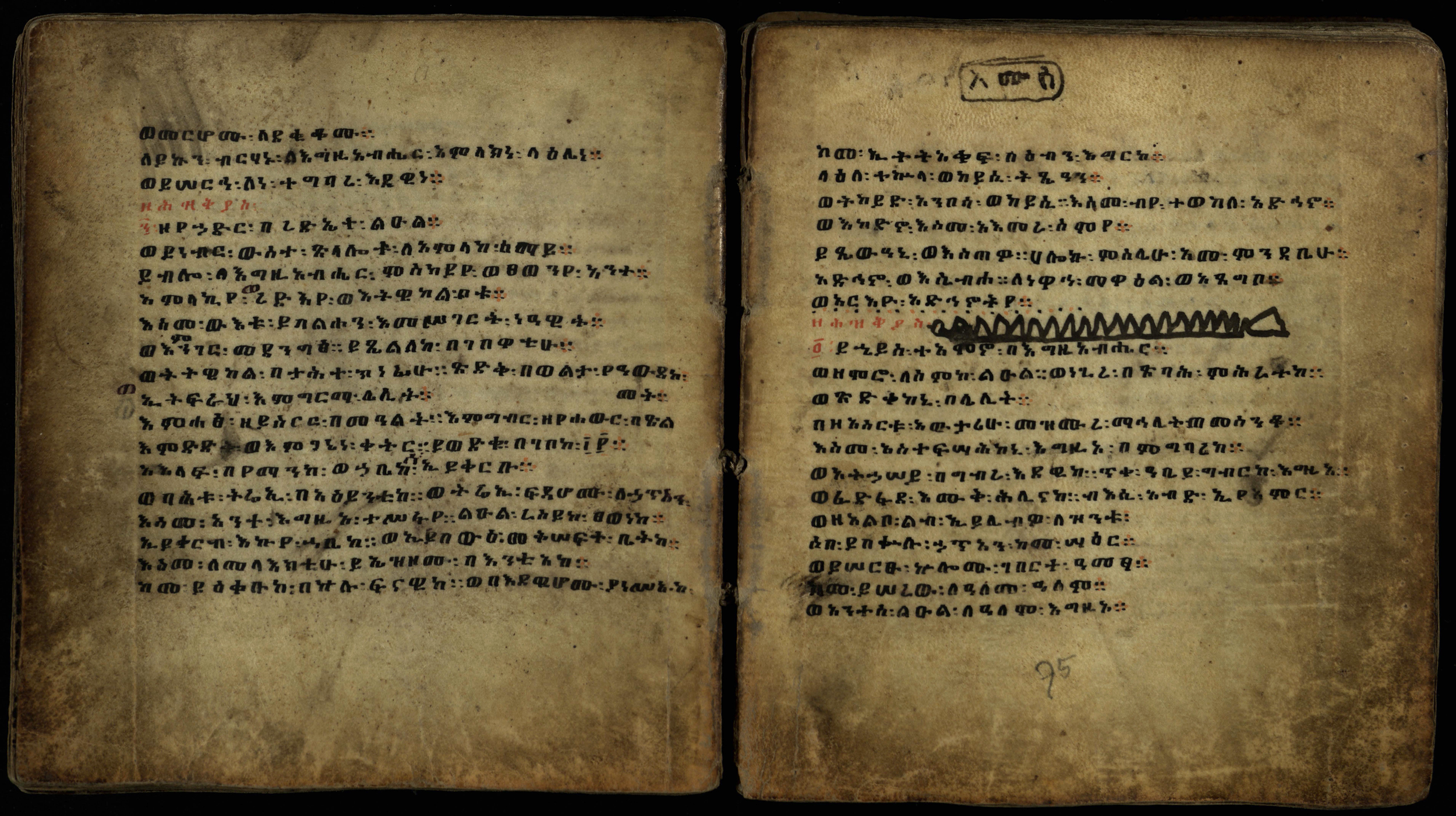

The psalter is written in Ge’ez, the language used when the Bible was first translated from the Greek in the 5th century, rather than Amharic, the language of modern day Ethiopia. The text includes the Psalms, traditionally ascribed to King David, prayers of Moses, hymns to the Virgin Mary, and personal notes in a less formal hand at the beginning and end of the book. The striking images seem very different to those we are used to in Western religious manuscripts, yet they show the influence of European ideas.

The image of King David with his Eastern harp is different in style but very similar in content to the King David in our own 15th c English psalter (pictured left); both have servants in the background although our David didn’t need the fly whisk.

Having been on holiday to Ethiopia this January, I was intrigued to see how very alive this artistic tradition still is, in the form of religious texts, icons, church paintings, monastic decoration and tourist souvenirs. Religious observance is still very strong both in the Orthodox Christian and the Muslim communities; I visited at the time of Orthodox Christmas (7th January) and shared the celebrations with thousands of white-clad pilgrims and a multitude of chanting priests amongst the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela.

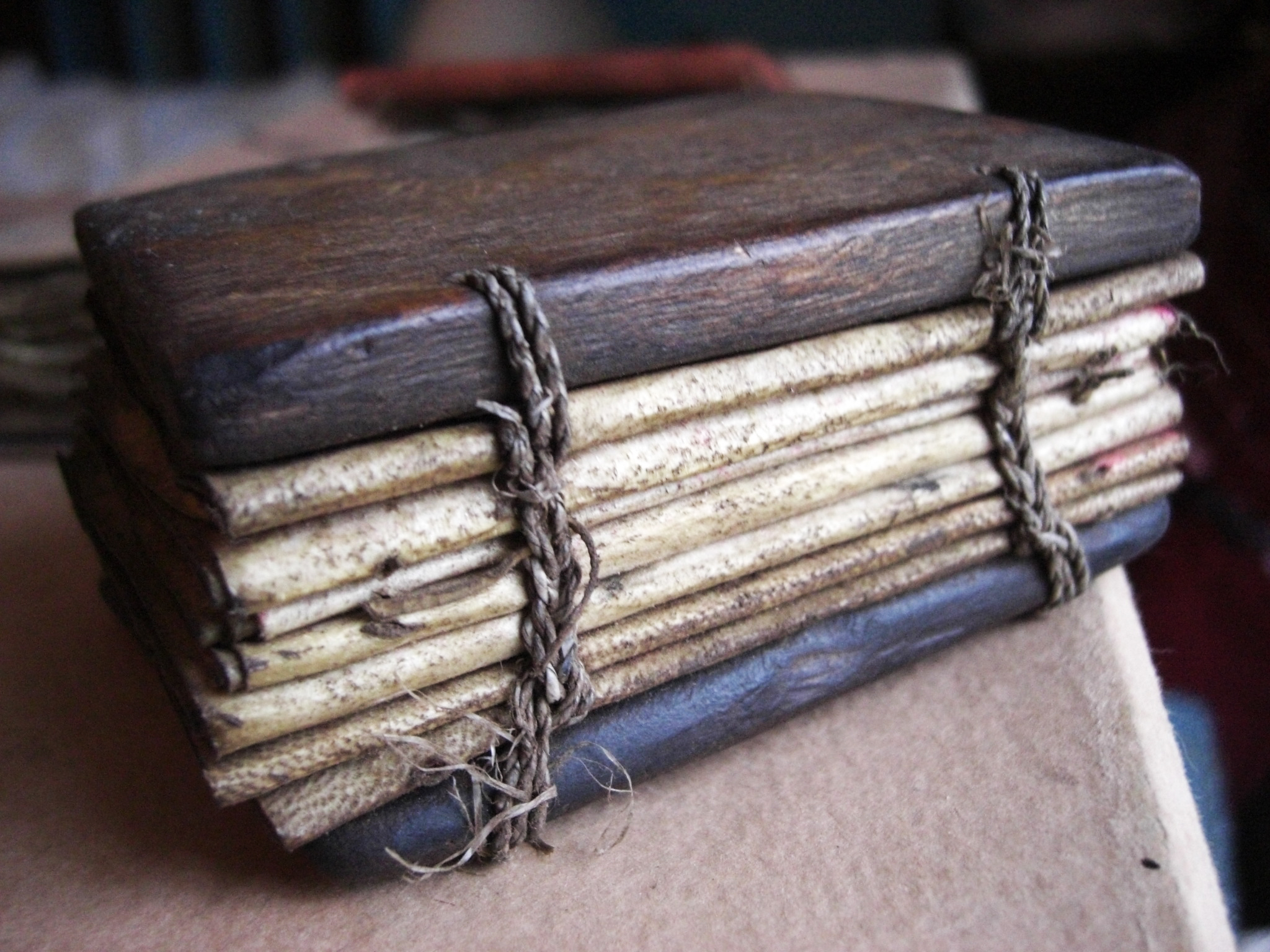

In the market here were numerous modern reproductions of icons and manuscripts featuring illustrations very similar to those in the Psalter. Two sorts of traditional manuscripts are still being produced – the codex for religious works, and long strips of parchment inscribed with magic devices and spells carried as an amulet. Special Collections also owns one of these scrolls.

In this distinctive religious iconography angels are very popular, and many icons and wall paintings in churches feature the Archangels Gabriel and Michael, as well as numerous saints, especially St George killing the dragon. The cult of Mary ensures ubiquitous Madonna and Child portraits as well as scenes from the life of Mary and in particular the flight to Egypt which is believed by Ethiopians to have been via their own country.

The psalter is thought to date from the 18th century although it is very hard to date these manuscripts. The illustrations appear to be more recent additions, although their position at the start and end of the text rather than within the text is traditional. Their iconography is conservative, but the intensity of the colours, lack of dirt and hints of writing underneath some of the paintings suggest they are copies of older works, or a refreshing of the original paintings, a process seen in the monasteries of Lake Tana – their richly, almost overwhelmingly, decorated walls have been restored, copying faithfully the style of the earlier paintings.

The wooden covers have both been mended, one with strips of leather, the other with copper wire. The parchment is probably goat. The binding with link-stitch thread, made traditionally of animal tendon, now of cotton, linen or synthetic string, is still in use today as on this manuscript from Lalibela market. The text is in black ink with important words such as nomina sacra and headings in red, as well as to emphasis punctuation, with ornamental bands are used on important pages.

It is now illegal to take ancient manuscripts out of the country, as so many have been lost, sold or stolen over the years. They are prized by their monastic owners and kept carefully in locked cabinets and treasuries, such as this library full of cloth covered volumes at a Lake Tana monastery. The power of the sacred texts is still respected and sought out – the photograph featured on the left shows a priest blessing a woman with a copy of the gospels on her back, in a ceremony to bring her fertility.

From a similar part of the world we also have a Coptic psalter, written in Egypt, which is quite different in style.

To see digitised Ethiopian manuscripts, check out the Ethiopian Manuscript Imaging Project on the Vivarium website.

–Maia Sheridan

Manuscripts Archivist

Discover more from University Collections blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Reblogged this on Imbuteria's Blog.

Pingback: 52 Weeks of Inspiring Illustrations, Week 38: Angels, Madonnas and Pilgrims — an Ethiopian treasure | Special Collections Librarianship | Scoop.it

Pingback: Folding Passion icon from Ethiopia, ca. 1900 | The Jesus Question

Pingback: On the etymology of شيطان ‘Satan’ in Arabic | burj bābil

I have a painting that my uncle (David Hamilton) bought when living in Ethiopia in the 1960s/70s. It consists of 44 pictures clearly telling a story, possibly biblical. there is writing above and below each picture, possibly in Amharic.

I have no idea how old it was when he bought it but would love to know its story. PLease can i send you a picture of it.

many thanks

Lucy