There is a scene early in Mansfield Park (1814) where Maria and Julia Bertram, then aged thirteen and twelve, deplore the ignorance of their slightly younger cousin Fanny Price. She cannot list the principal rivers in Russia, has never heard of Asia Minor, and doesn’t know the difference between water-colours and crayons; whereas for as long as they can remember they have been able to repeat the chronological order of the kings of England and Roman emperors, with dates of their accessions, and reel off ‘all the metals, semi-metals, planets, and distinguished philosophers.’ This satirical sketch of the essential accomplishments of a well-brought-up young lady reflects a large body of educational manuals and textbooks as well as a wider debate about the nature and purpose of female education. For this week’s blog post I wanted to focus on one aspect of this debate: what young ladies ought to read, according to a popular and important conduct book written at the end of the eighteenth century.

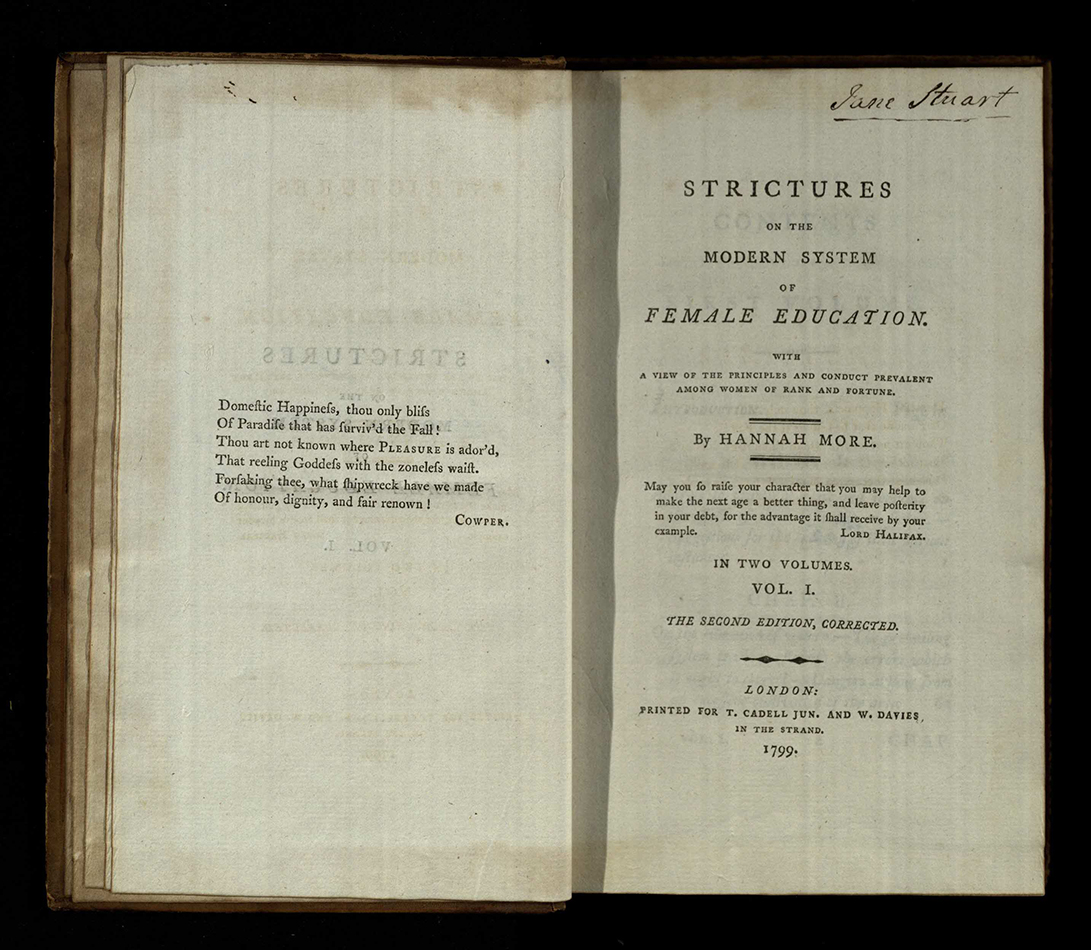

Hannah More’s Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education was first published in two volumes early in 1799, and seven editions were printed in the first year alone. This copy of the second, corrected, edition is from the library of James David Forbes.Both volumes have his armorial bookplate, but the signature on the title page is that of Jane Stuart, his grandmother. The first volume is inscribed on the front free endpaper: ‘With Mr Henry Thornton’s Compliments’. I haven’t yet verified the handwriting, but if this is the Henry Thornton who was a member of the Clapham Sect, close friend of both Hannah More and William Wilberforce, then there is a tantalising potential connection between Forbes’s family and More’s circle.

In 1799 More (1745-1833) was already well-known as a writer, dramatist and second-generation bluestocking, and she had a lifelong interest in education. The fourth of five sisters, her conspicuous passion for learning led her classically educated father to progress from telling her stories of Greek and Roman history to teaching her Latin and mathematics from the age of about eight. But her aptitude seems to have dismayed him (according to her first biographer Jacob More had a ‘strong dislike of female pedantry’) and the lessons stopped. In 1758 the eldest More sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, opened a boarding school for young ladies in Bristol, and Hannah attended as a pupil before becoming a teacher there. Her first publication, the pastoral drama The Search after Happiness, was originally written for the girls at the school to perform; it includes a passionately ambitious character who dreams of bursting female bonds and finding fame as a scholar, who is counselled by the ancient shepherdess Urania that ‘Science for female minds was never made’. In 1789 More and her sisters set up the first of a series of Sunday schools where poor children were taught to read (though, on principle, not to write). Strictures was her definitive work on education, and it sharply criticizes the deficiencies in contemporary female instruction.

Chapter VII addresses ‘female study, and initiation into knowledge’. Here More reviews various types of reading, drawing a strong formative connection between what girls read and their habits of mind and character. She doesn’t recommend any specific books ‘which are useful in general instruction’, as there is such an excellent variety that a teacher can hardly fail to make a beneficial selection, but she cautions against the danger that reliance on these elementary texts may make children lazy.

‘Where so much is done for them, may they not be led to do too little for themselves?’ (p. 168)

And she also points out a moral disadvantage, that this may lead children to believe that learning may be acquired without any effort, where all worthwhile knowledge is difficult to acquire. Similarly she is concerned that the profusion of ‘little, amusing, sentimental books with which the youthful library overflows’ (p. 170) may put children off more serious study which will seem uninteresting by comparison, and also that they might encourage spurious goodness rather than genuine charity. Frivolous reading from circulating libraries is frowned on too. And she attacks anthologies: ‘The swarms of Abridgments, Beauties, and Compendiums, which form two [sic] considerable a part of a young lady’s library, may be considered in many instances as an infallible receipt for making a superficial mind.’ (pp. 173-4). I had fun tracking down examples from the 1790s of the offending genre in our collection:

So, if you want to improve your mind, what should you be reading instead? More advocates books which ‘exercise the reasoning faculties’ and ‘would help to brace the intellectual stamina’. She warns timid young ladies not to start at her recommendations: ‘such strong meat as Watts’s, or Duncan’s little book of Logic, some parts of Mr. Locke’s Essay on the Human Understanding, and Bishop Butler’s Analogy’ (p. 179).

This is a formidable course of reading, and recalls the girl whose precocious talent for mathematics intimidated her father. More declares that she has no wish to encourage ‘scholastic ladies or female dialecticians’, but argues that thorough study of this kind of ‘dry, tough reading’ would check rather than induce intellectual conceit, through regulating and informing the mind. She does not exclude ‘works of taste and imagination’, but suggests that they should not comprise the whole of female reading and study. More can be a problematic writer for the modern reader, and she quotes Swift almost approvingly to depress female vanity in scholarly achievements: ‘that after all her boasted acquirements, a woman will, generally speaking, be found to possess less of what is called learning than a common school-boy.’ But her sustained contention that young ladies should be encouraged to engage with challenging reading, and develop their intellectual abilities, is invigorating.

–Elizabeth Henderson

Rare Books Librarian

Discover more from University Collections blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.