This is the second post in a weekly miniseries about advertisements in 19th century books. You can read the first post in the series here.

The Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire, commonly known as “Lodge’s Peerage”, was a comprehensive genealogical directory to Britain’s nobility published from 1829. Edmund Lodge, like his contemporary John Burke, was a respected genealogist, but his involvement in the compilation of the Peerage was minimal; the majority of the work actually being undertaken by three women: Anne, Eliza, and Maria Innes.

The advertisement section at the end of this weighty document spans 26 pages and touts everything from life insurance to snake oil cures; home appliances to firearms (“…the most perfect and safest Guns ever introduced”). Since the Peerage intended to provide the most accurate information about the upper echelons of British society, it was continuously updated and new editions were published regularly; thus, these advertisements can truly be considered ephemera, providing brief windows onto the world of retail and commerce in the nineteenth century.

But alongside the notices of fruit lozenges and tooth-whitening creams are several fundraising announcements for charitable organizations. This short blog post will consider what these memoranda can tell us not only about life in Victorian Britain, but also something of the values and moralistic concerns of the people who purchased these books.

Established in 1856, the Royal Northern Hospital, then known as the Great Northern Hospital, was ideally situated at King’s Cross, London. The arrival of the railway terminus resulted in a booming, and increasingly impoverished, population in this neighborhood. “The demands of the Sick Poor in this large district are far beyond the means at the disposal of the Committee,” the advertisement reads. “AID is earnestly solicited to meet pressing demands.” When this edition of Lodge’s Peerage was published in 1861, the hospital had only been operating for five years and seems to have been keen to advertise its successes to potential benefactors. “Cases relieved during two years, 109,660,” it trumpets. “Weekly, between 700 and 800.” The railway’s rapid expansion forced a move to Holloway Road in 1888.

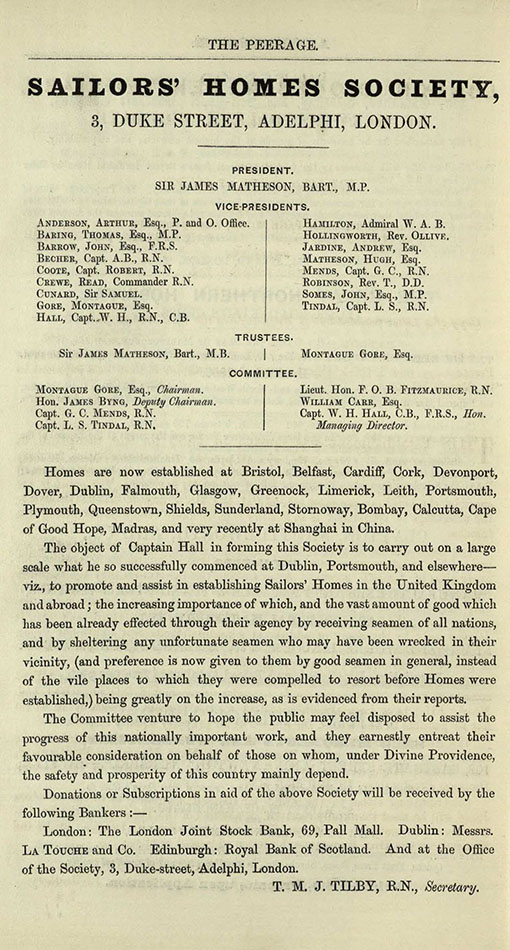

The Sailors’ Homes Society established institutions for destitute seamen at the major British seaports as well as in the farflung reaches of the empire, like Bombay (Mumbai) and Shanghai. These homes accepted men of all nationalities who landed in these ports, and catered especially those “who may have been wrecked in their vicinity”. As testimony to the success of these foundations, the advertisement observes that even “good seamen in general” now prefer to lodge there, shunning the “vile places to which they were compelled to resort” in years past. While moral anxiety about the legendary behaviour of sailors in port towns may have contributed to the development of these benevolent societies, this notice is eager to emphasize the “nationally important work” of providing for these men upon whom “the safety and prosperity” of Britain depended.

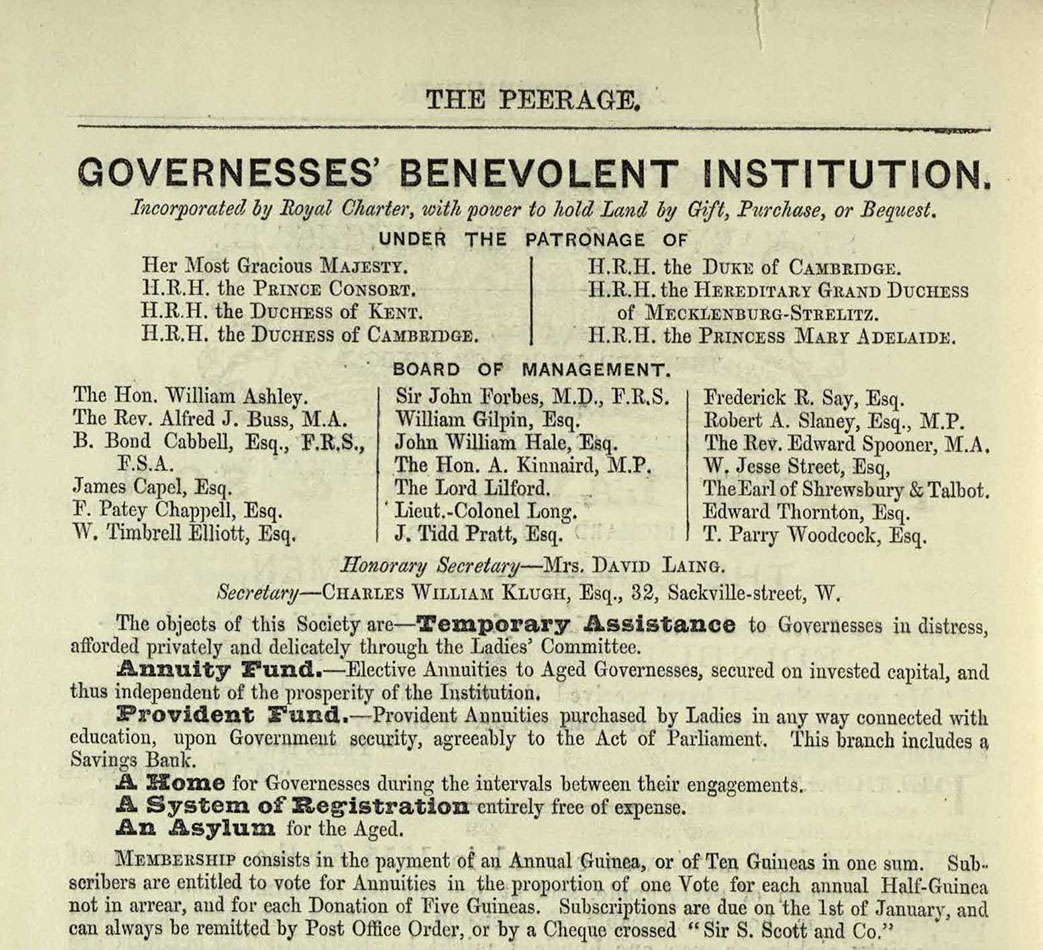

Founded in 1841, the Governesses’ Benevolent Institution assisted these professional women particularly in times of illness and old age. Like the Sailors’ Homes, this organization provided food and shelter as well as financial assistance to women in between jobs. It also provided for retired women and encouraged those still in professional life to purchase annuities through the institution’s own Savings Bank. Many such women, without family to depend on, surely benefited from this enterprise. But governesses were not the only women deemed worthy of such charity.

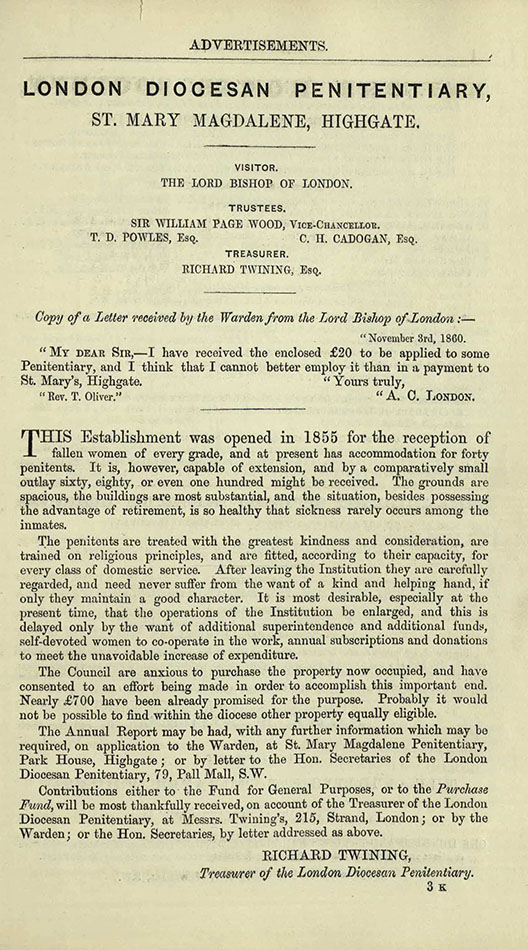

The London Diocesan Penitentiary, or St Mary Magdalene House, opened its doors in 1855 to the metropolis’s “fallen women” with the aim of returning them to the righteous path. For the reformed prostitutes and other unvirtuous women who were received there, the institution provided not merely food and shelter, but perhaps more importantly to its benefactors, religious instruction and training for domestic service. This full-page advertisement was part of a fundraising scheme undertaken by the trustees to secure their property at Park House, Highgate, which they eventually purchased later in 1861. During this time charities for fallen women, and St Mary Magdalene House in particular, were a kind of cause célèbre among the Victorian upper classes and literati; indeed, poet Christina Rossetti actually volunteered at the penitentiary, where she was known to the inmates as Sister Christina.

Perhaps the most affecting of these notices is also one of the briefest. The Dudley Stuart Nightly Refuge operated as a homeless shelter during the winter months for London’s poorest citizens. Images of similar charities show dark, crowded spaces sparsely decorated with simple furnishings. These and other examples speak vividly to the city’s growing inequality in the Victorian Age.

So who exactly was the target audience of these advertisements? In the face of unprecedented wealth disparity, philanthropic giving became a cornerstone of the emerging Christian, bourgeois Victorian identity. Whether through images of hardship and suffering, or appeal to a sense of moral and national duty, the trustees of institutions such as these sought contributions from the aspiring middle- and upper-classes to a variety of worthy causes.

-Emily Savage

Lighting the Past Cataloguer

Emily Savage is in the third year of her PhD at the School of Art History. She studies the relationship(s) between gender and viewership, and their impact on the experience of art in late medieval England.

Discover more from University Collections blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

So now I understand where the curious word antimacassar comes from.

For the sake of argument, Christianity is not the only ‘religioun’ with moral high-grounds’.. now or then, but I do understand that is about the history of England, which was built on the Protestant culture.

Pingback: Adverts in 19th century books: “AID is earnestly solicited” – Advertising for Charitable Organizations in the Victorian Age — Echoes from the Vault – internationalnews1990.worldpress.com

Pingback: Birth of American Bee Culture : A Look at Advertisements in A.J. Cook’s The Bee Keepers’ Guide | Echoes from the Vault

Wow, how random is WordPress, love it, very interesting stuff, that’s a follow from me.