In this blog, masters student Ellen Robertson takes a look at a copy of the ‘The whole booke of Psalmes’ in University Collections, which formed part of her studies on the MLitt programme The Book. History and Techniques of Analysis.

‘Therefore, after thoroughly searching everywhere, we will find no better songs nor more appropriate ones than the Psalms of David’ wrote John Calvin in 1543 (Maag, p. 29). This sentiment, popularized by Calvin, resulted in many editions of metrical psalters, including the 1583 copy of Sternhold, Hopkins, and Whittingham’s The Whole Book of Psalmes, collected into Englishe metre found in the University of St Andrews University Collections.

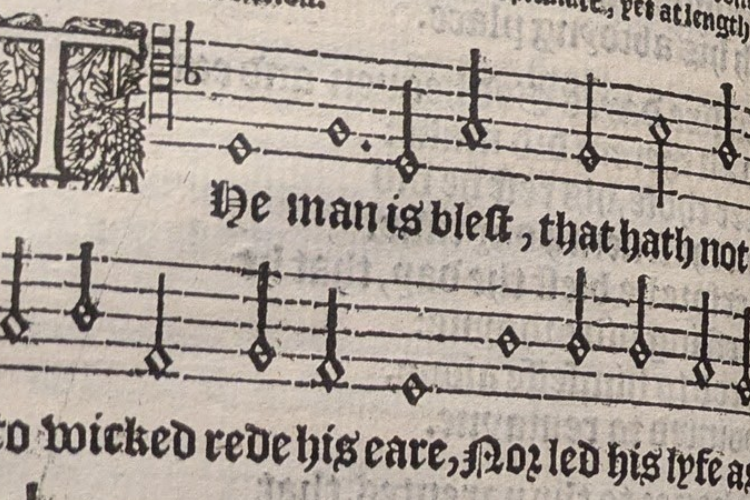

This quarto edition, printed by John Day, includes common prayers and songs, all 150 psalms in meter (some with musical notation), and ends with more prayers and a table of contents. The music is notated in a modernly recognizable format with staves of 5 lines and single notes placed appropriately. This was printed with musical type consisting of long horizontal lines for the staff where there was not a note and notes with horizontal lines properly spaced to match the rest of the staff. This allowed the music to be set just like the rest of the letter press type. The text to be sung is set below each staff under the relevant note(s).

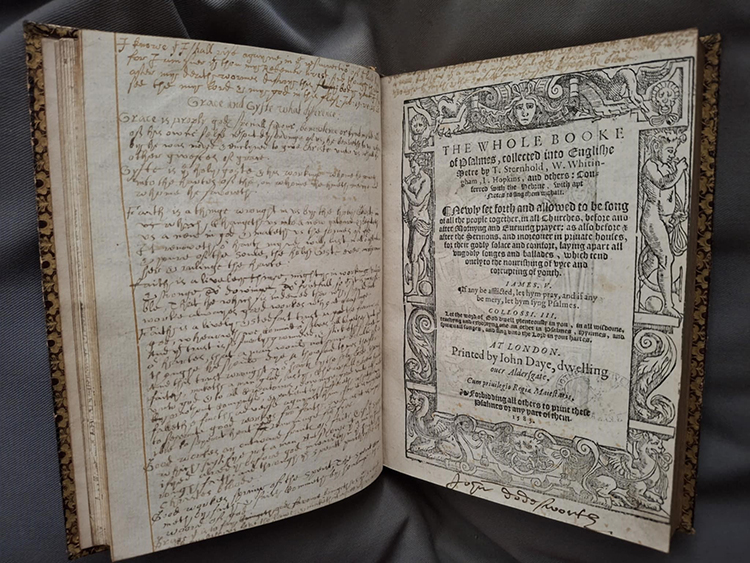

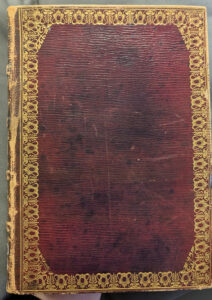

The particular copy of this edition in the St Andrews library is bound with 15 leaves of blank paper before the printed text and 14 after. Some of these blank leaves have the same jug and crown watermark as the pages of letterpress. Therefore, it is likely that these leaves have been with the book since it was printed. About half of these leaves have English manuscript notes, which vary between secretary and italic writing, in at least two different hands and in many different inks. Most of these notes are related to the Christian faith, but do not comment upon the Psalms. The handwriting that covers the majority of the leaves continues onto the printed pages, meaning the writing happened after the book was printed in 1583. ‘John Dodesworth’, presumably a former owner of the book, is written at the foot of the title page. The Harleian-like binding (red morocco with gold tooling around the edges) was popular in the mid-18th century, and the fact that the pages are trimmed indicate this book was likely rebound and the page edges gilded after almost 200 years of use.

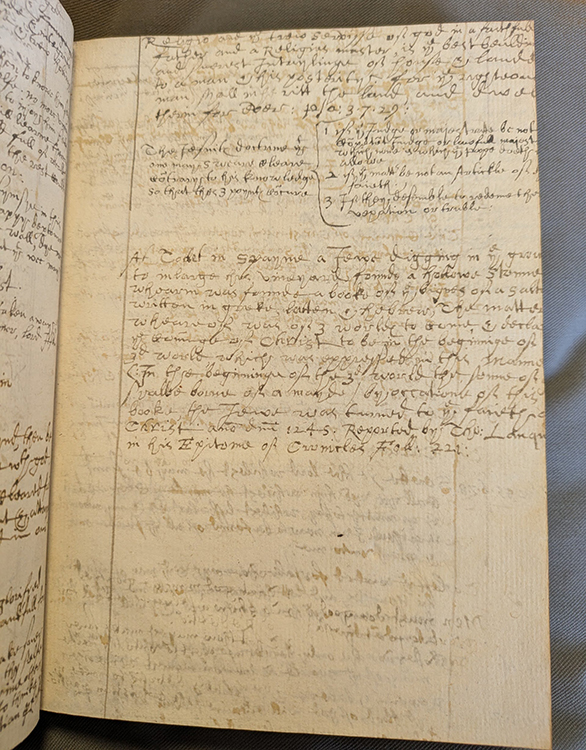

The manuscript notes begin with ‘ano dom. 1518: Marten Leuther in Jarmany doth preche the gospell’. This is representative of the clearly Protestant tone of the rest of the book, both the printed and manuscript parts. The notes contain many summaries/paraphrases of specific scriptures including: John 3:16, Romans 8:28-29, Ezekiel 33:1, Isaiah 55:6-8, Job 19:25-26, and Psalm 37:29. Interestingly, many of these verses are still popular to memorize and quote today. There are several pages with passages that look like poems or sayings about aspects of the Christian life, such as not fearing death, understanding faith and grace, describing the church, and teachings on how to pray. In addition, the notes include statements, repeated in multiple locations, describing baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and the essentials of the Gospel message in the form of a testimony. The verso of the title page has calculations for the number of years between different Biblical events.

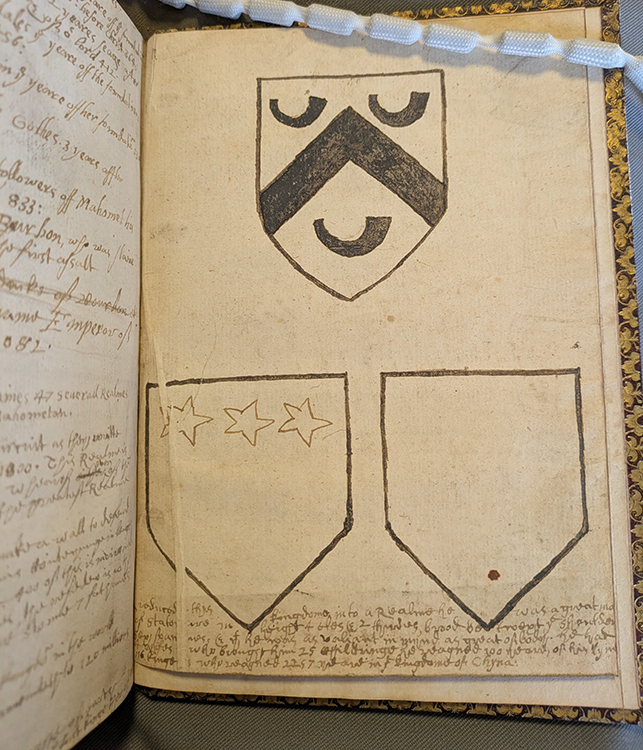

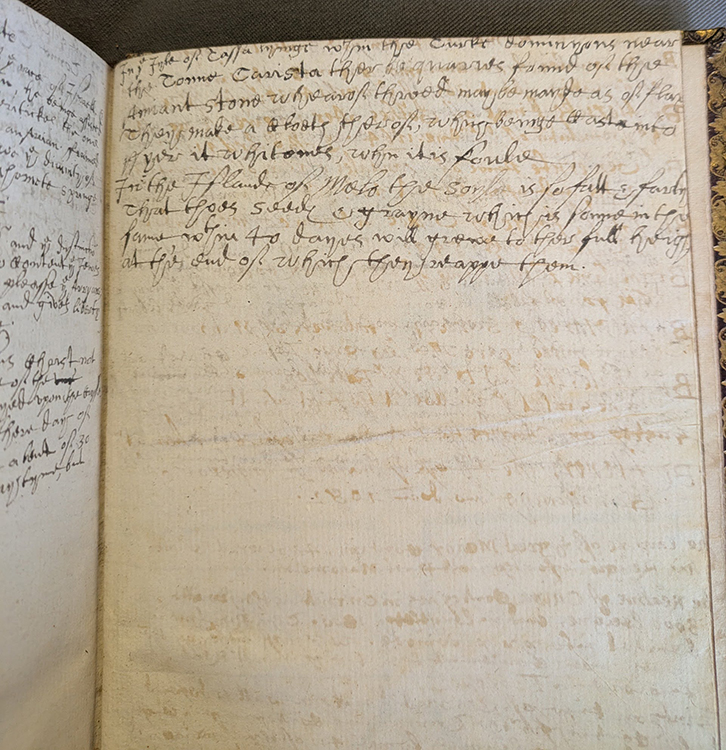

The last several manuscript leaves discuss various foreign curiosities such as details about the ‘Pyramides of Egipe’, the history of Islam, the history of the realm of China, and when and by whom Rome was sacked. On the final leaf there is a hand drawn shield with the Dodsworth coat of arms, a chevron and three bugles.

While some notes are not obviously related to the Christian faith, they may have had some Christian meaning to the writer. One page has a paragraph describing a cloth made of Amiant stone from Carista that can be cleaned and whitened by casting into the fire. This is a description of cloth made from asbestos out of quarries near Karystos in Greece. This concept of cloth that whitens when burned is similar to the concepts in Revelation 3:18, Daniel 7:9, and Mark 9:3.

Two different leaves, one before and one after the printed text, contain a story about a Jew in Spain in 1245 who converted to Christianity because he found a book of prophesy in a hollow stone in the ground. The writer, in both instances, cited Thomas Lanquet’s An Epitome of Chronicles fol. 221 as the source of this story. The manuscript is indeed copied word for word, though the spelling varies from the 1549 edition. The writer(s) of all these manuscript notes was a collector of information and looked for meaning in world events and theological issues.

The metrical Psalms were a very popular concept throughout the Christian world. John Clavin, Desiderius Erasmus, Clément Marot (valet de chambre to Francis I of France), Thomas Sternhold (courtier to Henry VIII of England), and others recognized the impact of music in people’s lives and rewrote the Psalms so they would rhyme and be more conducive to singing. Sternhold used a ballad meter familiar to the people and his publication included 19 Psalms. Reverand John Hopkins and William Wittingham continued ‘translating’ more Psalms into meter and included them in the publication (although Wittingham’s goal for his compositions was translational accuracy rather than ease of singing). Sternhold and Hopkins’ All suche Psalmes was the ‘most frequently re-printed publication of Edward’s reign’ (Duguid, p. 5; Weir, pp. 153-154). The Universal Short Title Catalogue has roughly 650 editions of Sternhold, Hopkins, and Whittingham’s The Whole Book of Psalmes collected into English metre published between 1550 and 1700. In 1583, John Day of London, who held the lucrative privilege for printing metrical Psalms in England, published 9 editions of Sternhold’s The Whole Book of Psalms in a variety of formats, including folio, quarto, octavo, and 16mo.

In London, Day’s printings of Sternhold’s Whole Booke of Psalmes must have resulted in many thousands of books. An analysis of the copy held at St Andrews epitomizes the meaning an individual copy of these ubiquitous books had for its owner. The manuscript notes show study and investment in the Christian life, even if they do not engage with the specific printed text. The rebinding and gilding, inclusive of the manuscript pages, speaks to the fact that someone valued this book and the notes in it.

Ellen Robertson

Select Bibliography:

Printed Primary Sources

Burke, Bernard, The general armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales; comprising a registry of armorial bearings from the earliest to the present time (London, 1884).

Lanquet, Thomas, An epitome of chronicles, (London, 1549).

Sternhold, Thomas, Whitingham, William, Hopkins, John, The Whole Booke of Psalmes, collected into English Meter, (London, 1583).

Secondary Sources

Bennett, Henry, ‘Sternhold, Thomas’, in Sidney Lee (ed.) Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol 54 Stanhope – Stovin (London 1898), pp. 223-224.

Duguid, Timothy, Metrical Psalmody in Print and Practice (New York, 2014).

Evenden, Elizabeth, ‘Patents and patronage: the Life and Career of John Day, Tudor Printer’, (PhD Dissertation, University of York, 2002).

Evans, John, ‘The Identity of the Amiantos or Karystian Stone of the Ancients with Chrysotile’, Mineralogical Magazine and Journal of the Mineralogical Society, 14, no. 65 (1906), pp. 143–148.

Garside, Charles, ‘The Origins of Calvin’s Theology of Music: 1536-1543’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 69, no. 4 (1979), pp. 1-36.

Gilroy, Clinton, The history of silk, cotton, linen, wool, and other fibrous substances (New York, 1845).

Maag, Karin. ‘”No Better Songs”: John Calvin and the Genevan Psalter in the Sixteenth Century and Today’, The Hymn, 68, no. 4 (2017), pp. 28-33.

Nixon, Howard and Foot, Mirjam, The History of Decorated Bookbinding in England (Oxford, 1992).

Weir, Richard, ‘Thomas Sternhold and the Beginnings of English Metrical Psalmody’ (PhD Dissertation, New York University, 1974).

Internet Sources

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Clément Marot’, Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 August 2024, <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Clement-Marot> [accessed 18 April 2025].

Pettegree, Andrew, ‘Day [Daye], John (1521/2–1584), printer and bookseller’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sep. 2004, < https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-7367> [Accessed 18 April 2025].

Universal Short Title Catalogue, 2025.

Discover more from University Collections blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.